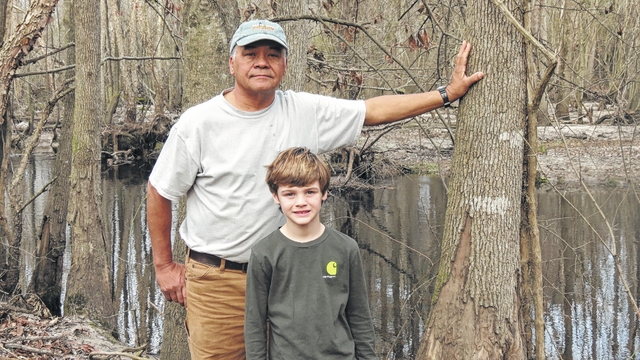

On a warm sunny afternoon, you can find Philip Bell and his grandson, Brennan, floating down the black waters of the Great Coharie River. For years, the river served as a lifeline for the Coharie people, once supplying sustenance for the tribal community.

Today, those waters are just as black, but have lost much of the luster and life that once brought great food, spiritual healing and other resources to the people of the land.

Growing up, Bell said the river was open, flowing from just outside of the Newton Grove area and dumping into the Black River in southern Sampson County and eventually into the Cape Fear River. The banks of the river were lined with Pin Oaks, Water Oaks and Chestnut Oaks and served as a source of food for the game.

“When I grew up, the river was open and you could see down through the woods for a long distance,” Bell said, sharing the fond memories he had as a child going to the river for fun, food and even baptisms.

According to Bell, along the Great Coharie was the perfect spot for wildlife to live. The fishing was abundant, providing many meals for those of the Coharie community.

“There are areas named for different people,” Bell said. “There was a time when we would go down to the river for baptisms. Most of the people who lived in the area used the river for sustenance. Not anymore.”

That abundance of fish brought the community together.

“We would set a trap in the river, catch a bunch of fish and hold a community fish fry,” Bell said.

Not only did the river bring food, but wood to burn in home in the winter to help families keep warm and at Christmas, trees to put up in homes to help in celebrating the holiday season. No more — the river doesn’t afford today’s generation with what Bell grew up thinking was a part of life.

“The river was our recreation department,” Bell said with a laugh. “We didn’t go to town and play on some sports team. You were lucky if you finished all the work in the field, and all your chores around the house and your daddy let you go down to the river with friends.”

The river offers solitude for many, a treatment for one veteran who suffers from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

According to Bell, a retired military veteran was observed visiting the river on a regular basis after the first portion of the water was opened. Over the last couple of years, Bell said the veteran logged many miles and hours on the river. During a luncheon last spring, the veteran was talking about the river served as a form of therapy for his disorder and how he was able to take less medication for his PTSD from the war.

This, Bell said, was the life — the life before the beavers.

In the early 1970s, beavers began to over populate the river and it’s surroundings. Over time, the population continued to grow and the beavers became a nuisance. For a few years, the county had a bounty on beavers, but that didn’t last long and the number of animals and dams continued to grow.

A trapper was hired by the county, and that, Bell said, helped keep the numbers down, but in time the population outgrew the number of beavers being trapped and dams being destroyed. The fur trade industry waned, and with the expanding population the river was overtaken by beavers and their homes.

The destruction and devastation in the river only continued, when in 1996, the area was hit by Hurricane Fran, toppling trees throughout the river’s banks and blocking the once open path of the Great Coharie. Just three years later, in 1999, Hurricane Floyd hit the already damaged area, causing more damage to the river banks and knocking more trees down across the river.

By this time, between the beavers and the trees, Bell said the river was unusable. The river that was once a part of the livelihood of the Coharie people, was now nothing more than piles of trees and a breeding ground for thousands of beaver families.

“Over time, the river became a beaver haven,” Bell said. “It wasn’t being used by the community anymore and what I once knew as being a part of my childhood was no longer a part of anything.”

Following Fran and Floyd, FEMA came in and cleaned out some of the river’s area, but nothing close to what it was just 20 years before. In 2014, the United States Forestry Service began helping the Native Americans manage forest land, and the river was part of that area.

“The damage from the storms created havoc on the river,” Bell explained. “There was a total annihilation of the forest canopy.”

As a child, Bell said he remembers going down to the river’s banks and gathering blueberries, grapes and honeysuckle. Now that the river’s canopy was gone, that vegetation couldn’t grow anymore and the land was not productive.

In 2015, the Coharie Tribe became part of the Great Coharie River Initiative, a restoration effort that had the hopes of creating a navigable pathway through the upper Great Coharie, a part of the river just off of U.S. 421 that runs through the heart of Coharie land.

Members of the Coharie Tribe, friends, community members and members of the Friends of Sampson County Waterways joined and cleaned nearly two and half miles of the river. In 2016, a grant was awarded and more equipment was purchased, allowing for another two and a half miles of the river to be cleared.

According to Bell, from Five Bridge Road to an area past Keener Road was clear and open for the community, tourists, adventurists and anyone wanting to take a trip down the river. The Great Coharie River spans about 43.5 miles and eventually, Bell said he would like to see the entire area clear, so that someone could easily go from Sampson County to the coast via the water.

All of the hard work and manpower was erased last fall when Hurricane Matthew dumped inches of rain and toppled trees, leaving the river in the condition it was in just a few years earlier.

“We basically have to start over again,” Bell said. “Matthew littered the river, downed trees and left piles of debris. There are areas that have been filled back in.”

At the least, Bell said Matthew’s damage will take a year to clean up, but possibly more. Cleaning up the river is a fight Bell feels is worth the work and time.

“When we started this, my goal was to be able to take my grandson into the river like I did as a child,” Bell explained.

Bell posses a strong passion for the river and the project. The river, he says, is much more than waters flowing between river banks and trees. It’s a valuable item that is beneficial to not only the environment, but the people who surround it.

“The river is what we need in our community for the kids,” Bell said.

At it’s peak, Bell said people were out on the river almost every day, using the water for relaxation and the many other benefits it provides. People from not just Sampson County, but neighboring states have used the river for recreation. At its best, Bell says the river is not just a benefit to the people, but the environment and animals who surround the banks of the river and fill the depths of the water.

For now, Bell says he will continue to fight for grants to help go in and clean up the water. He is also a strong advocate for some type of beaver management plan that will allow people to want to go into the river and open the water for traveling up and down the Great Coharie River.